WANG MUTI: The First Taiwanese Solo Show at The National Art Center, Tokyo — Writing the Next Chapter of the NAU Avant-Garde Legacy

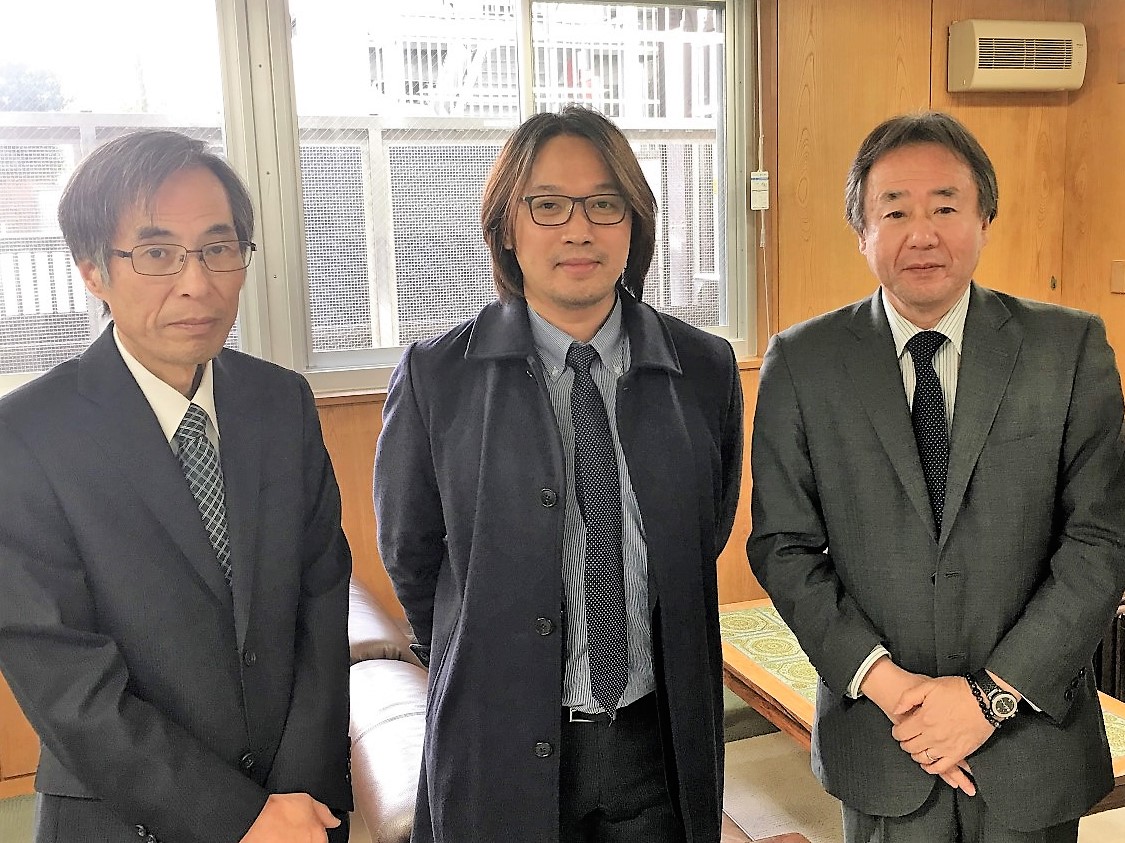

Text / International Art Feature Reporting Team

Historical Coordinates: A Taiwanese Artist’s Breakthrough at the National Art Center, Tokyo

Early Spring, 2026. Roppongi, Tokyo.

As winter sunlight penetrates the iconic undulating glass curtain wall of The National Art Center, Tokyo (NACT), casting shadows on the massive inverted conical concrete columns, this supreme hall of Japanese art welcomes a historic moment.

In the highly anticipated "24th NAU 21st Century Art Renritsu Exhibition," Taiwanese artist Wang Mu-Ti has been invited to participate. Unlike standard participants, he has broken the convention of "single-piece display" in large-scale public entry exhibitions, securing the privilege of an "Independently Curated Space." This marks him as the "First Taiwanese Artist" to hold a "Solo Exhibition Format (Solo Exhibition within a Group Show)" at the National Art Center, Tokyo.

This is not merely a participation; it is an "Establishment of Cultural Sovereignty." Wang Mu-Ti brings not scattered paintings, but three visual masterpieces approaching 4 meters in height, constructing a complete worldview—Form as Emptiness, Numinous Realm: Alishan, and Light of the Middle Way. He uses these works to implant a "spiritual island" of Taiwanese contemporary art within the core of Roppongi, creating a powerful dialogue with hundreds of works from around the world.

The Power Dynamics of Space — Benchmarking against World-Class Museums

To understand the weight of the title "Taiwan's First," we cannot view NACT merely as an exhibition venue but must benchmark it within the "Power Spectrum of World Museums."

Designed by the master of Metabolism architecture, Kisho Kurokawa, NACT is a singularity in Japan's post-war museum architecture history. It has no permanent collection, focusing solely on "exhibition." This characteristic of being an "Empty Vessel" places it internationally alongside top-tier institutions:

1. Grand Palais (Paris): The National Showcase

Just as the Grand Palais is the face of France for hosting top salons like FIAC and national special exhibitions, NACT is Japan's first choice for international touring blockbusters (such as Impressionist exhibitions or the Yayoi Kusama retrospective). It represents the Japanese official definition of the "highest specification" for art. For Wang Mu-Ti to secure a solo exhibition space here is equivalent to obtaining an independent booth at the Grand Palais Salon, symbolizing that the quality of his work has reached "National Specification."

2. Royal Academy of Arts (London): The Artist-Led Hall

NACT bears the responsibility of being the highest honorary hall for important domestic art groups in Japan (such as Nitten, Nika, and NAU). This aligns with the logic of the RA's "Summer Exhibition"—it is the highest coordinate for contemporary artists to prove they are "On-site." For Asian artists, securing a place here means entering the core vision of the Japanese mainstream art circle.

3. The Ultimate Challenge of Space: Japan's Premier National Museum

NACT boasts a massive scale of 2,000 square meters for a single exhibition hall, with a ceiling height of 5 meters. This industrial-level space is a brutal test for artists. If the "Physical Mass" or "Spiritual Tension" of the work is not strong enough, it will be instantly swallowed by the aura of the architecture.

Wang Mu-Ti's achievement lies in the fact that his works approach 400 cm in height. This massive vertical volume, like a monument, successfully "suppresses" this fluid space, transforming the giant white box into a personal dojo.

The Avant-Garde Genealogy — The Historical Soul of Japan's NAU

Another layer of strategic significance in Wang Mu-Ti's exhibition lies in his chosen organization—NAU (New Artist Unit). This is not an ordinary art group; it is the contemporary carrier of Japan's post-war avant-garde spirit.

The 1960s: The Wild Source of Neo-Dada

NAU's spiritual source can be traced back to the "Neo-Dada Organizers" that shocked the world in the late 1960s. It was a restless era where the Anpo protests coexisted with economic takeoff.

- Masunobu Yoshimura: The spiritual godfather of NAU and leader of anti-art. In the 1960s, he dragged art from museums onto the streets of Shinjuku, orchestrating radical performances.

- Ushio Shinohara: An avant-garde madman famous in New York for "Boxing Painting," representing the reverence for "Action."

2026: From "Destruction" to "Renritsu" (Alliance)

After half a century of evolution, Yoshimura's "anti-art" spirit has transformed into NAU's core philosophy today—"Renritsu" (Alliance/Standing Together). "Renritsu" implies independent individuals standing side by side in the same space-time while maintaining heterogeneity and not compromising personal style. This is a "Contemporary Art Commune" that no longer seeks a unified style but accommodates differences.

Wang Mu-Ti's Historical Positioning: The Intellectual Relay

As the first Taiwanese member of NAU, Wang Mu-Ti's joining marks the completion of an important piece of the "Asian Geopolitics" puzzle for this avant-garde group.

He did not choose to imitate the forms of Japanese Neo-Dada (such as destruction or performance art) but introduced his unique "Intellectuality." With a dual identity as a "Digital Museum Project Director" and a "Contemporary Buddhist Sutra Editor," he responds to the legacy of "Conceptual Art" left by NAU predecessor Shusaku Arakawa with deep conceptual frameworks and material experiments—art is not the display of a single medium, but a container for thought.

Micro-View — Deep Decoding of Three Masterpieces

In Exhibition Room 1A of the National Art Center, Tokyo, Wang Mu-Ti's three works form a complete narrative loop. All completed at the end of 2025, they demonstrate the artist's latest creative explosive power. These three works are all giant creations nearly 4 meters high, displaying extremely strong spatial command.

1. Form as Emptiness (〈空中之色〉) — Suspended Gravity and Material Paradox

- Dimensions: 139 (W) × 390 (L) cm

- Medium: Xuan paper, ink, acrylic paint

- Year: December 2025

This giant work, reaching 3.9 meters, has a strong visual impact. The subject is a massive, deep black mass, as if a rock dug from the depths of the earth's core, or a scorched organism. However, this heavy object defies the laws of physics, suspended in a background washed with acrylics in interwoven pastel purple and light blue.

- [Deep Critique]

- This is a dialectic on "Existence and Nothingness." Wang Mu-Ti uses the permeability of ink on Xuan paper to create the heavy, rough texture of the black mass, symbolizing the "Gravity" and "Karma" of the real world. The background creates a light, even virtual, emptiness. This precisely deduces the contemporary visual version of "Form is not different from Emptiness" from the Great Prajna Sutra—the heaviest matter actually floats within the lightest emptiness.

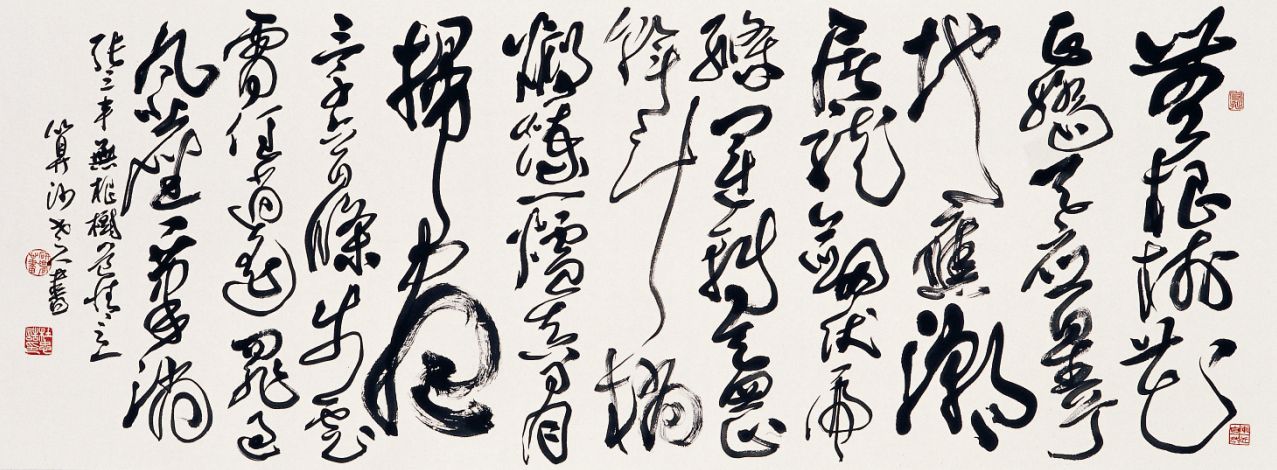

2. Light of the Middle Way (《中道之光》) — Geometry of Order and Spiritual Dimension

- Dimensions: 138 (W) × 390 (L) cm

- Medium: Xuan paper, ink, acrylic paint

- Year: December 2025

This is a Color Field painting in the style of Mark Rothko, but with a more Eastern ritualistic sense. The image is rigorously divided into three areas: top, middle, and bottom. The upper and lower ends are black-gold blocks full of material restlessness and metallic luster; the middle is a horizontal, mirror-smooth violet-white band of light.

- [Deep Critique]

- This is the final chapter of the trilogy, pointing directly to the "Middle Way" thought in Eastern philosophy. The chaos above and below coexists with the tranquility (order) in the middle on the same sheet of Xuan paper. Wang Mu-Ti's brilliance lies in not letting the band of light "eliminate" the darkness, but allowing the two to "Symbiose." This is a contemporary altarpiece, guiding the viewer's gaze from the restless edges to converge on the tranquility of the center, entering a meditative state.

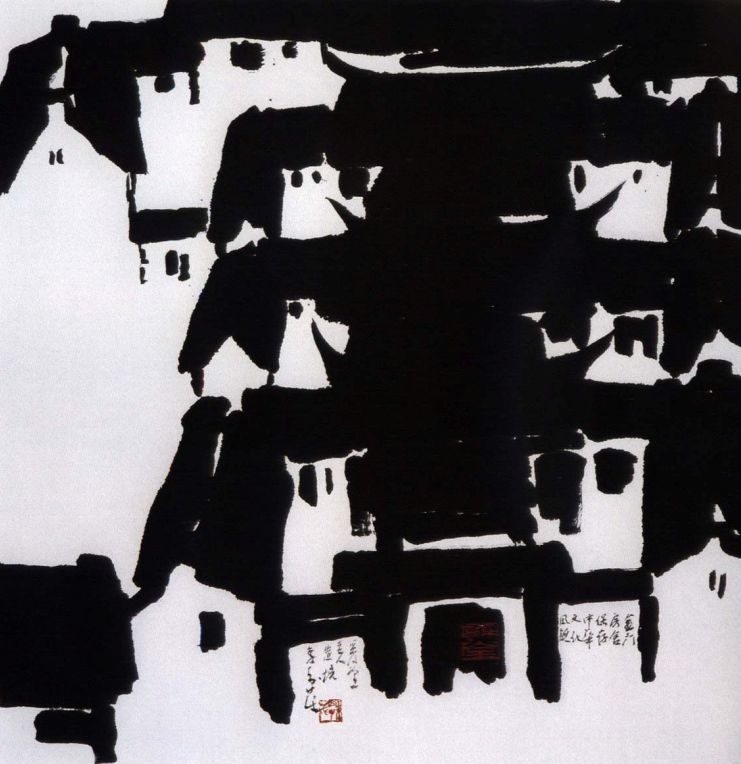

3. Numinous Realm: Alishan (〈聖境・阿里山〉) — Rubbing of Time and Sublime Aesthetics

- Dimensions: 142 (W) × 399 (L) cm

- Medium: Large-format Gasen paper (Produced by Ozu Washi), ink, acrylic paint

- Year: November 17, 2025

This work uses the extremely special "Ozu Washi Large-format Gasen paper," with dimensions approaching 4 meters high. The All-over composition is occupied by profound dark green and gray-black. It is not figurative leaves, but highly abstracted textures. Several sharp white lines penetrate vertically, like lightning piercing through fog.

- [Deep Critique]Wang Mu-Ti refuses tourist-style landscape depiction; he goes straight for the "Temporality" of the Alishan sacred trees. The unique fiber toughness of the large Gasen paper withstands the repeated stacking of pigments, forming a heavy texture like the bark of a thousand-year-old red cypress.

- In the context of art history, this is a display of "Sublime" aesthetics. Those vertical white lines are both the soul of the tree and the channel connecting heaven and earth. This work proves that through the translation of contemporary media, Taiwan's landscape can be sublimated into a universal spiritual totem.

Cultural Breakout from Periphery to Center

Tokyo's Roppongi in 2026 has added a spectrum from Taiwan because of Wang Mu-Ti's appearance. Utilizing the National Art Center, Tokyo as a world-class "Grand Palais," and integrating into NAU21, an avant-garde platform carrying the history of "Neo-Dada," he has successfully pushed the coordinates of Taiwan's contemporary art from the periphery to the center. He proves that a Taiwanese artist does not need to imitate Japan or cater to the West. As long as one honestly digs into the land beneath one's feet (Alishan), faces one's own culture (Middle Way philosophy), and possesses the ability to master huge scales and cross-media, one can prop up a sky belonging to Taiwan in the highest hall of world art.

When Clouds Fall on Canvas: Wang Mu-Ti’s "Digital Reaction" and Archival Painting

—— How does a Digital Museum Director use nearly four-meter masterpieces to resist the nihilism of algorithms?

At the site of Wang Mu-Ti's solo exhibition in Exhibition Room 1A of the National Art Center, Tokyo, the viewer's most intuitive feeling is "Weight." It is a heaviness coming from geology, from history, and from matter itself.

However, behind this heaviness hides a huge paradox: Wang Mu-Ti is not only an artist but also a senior "Digital Museum Project Director." He has assisted over 2000 artists in establishing digital databases and has long been dedicated to the digitization and cloud preservation of artworks.

Why does the person who understands "Virtual" the best make the most "Physical" works? This is the key to interpreting Wang Mu-Ti's exhibition.

Archival Consciousness — Viewing Painting as Storage Media

In today's world where Metaverse, NFT, and AI Generated Content (AIGC) prevail, images have become cheaper than ever. They are collections of pixels that are smooth, thickness-less, infinitely reproducible, and deletable at any time.

As a digital expert, Wang Mu-Ti knows the fragility of "Data" and the deception of "Screens." Therefore, he demonstrates a strong "Archival Consciousness" in his creation.

Refusing Smoothness: Tactile Resistance against Screens

The three works he exhibits this time all approach 400 cm in height, using a mix of Eastern ink and Western acrylics. This is essentially an "Anti-Digital" operation.

- Physical Irreversibility: Digital files can be "Undone" at any time, but the permeation of ink on Xuan paper and the stacking of acrylics on Gasen paper are irreversible. Wang Mu-Ti uses this irreversibility to leave traces of countless labors on the surface.

- Details Data Cannot Record: Standing in front of Numinous Realm: Alishan, you see complex micro-topographies produced by the blending of ink and acrylic. These details are random and organic, impossible to perfectly restore with any high-resolution scanner or 3D modeling. He creates a shock that "Can only be perceived when the body is On-site." This is a provocation to contemporary people accustomed to looking at art through mobile screens—you must come to the scene because the screen cannot transmit this physical mass.

The Curator’s Brush: Painting as Backup

Ordinary painters paint "scenery," but Wang Mu-Ti, as a curator, paints "physical backups of scenery." In Numinous Realm: Alishan, he does not depict the figurative appearance of Alishan but attempts to replicate the "texture" and "aura" of the sacred trees. The profound textures covering the canvas are like a "geological database" he established on the canvas. He attempts to seal that sublime spirituality into the fibers of the large Gasen paper, just as he seals artworks into servers. The difference is that servers store cold information, while canvases store warm "Aura."

The Echo of Avant-Garde — From Neo-Dada’s "Anti-Art" to Wang Mu-Ti’s "Anti-Algorithm"

The organization Wang Mu-Ti participates in, NAU (New Artist Unit), originated from the "Neo-Dada" of the 1960s. Back then, Masunobu Yoshimura used waste and street performances to resist the rigidity of traditional aesthetics. In 2026, Wang Mu-Ti inherits this avant-garde spirit, but the object of his resistance has changed. He no longer resists traditional oil painting, but resists "The Banalization of Algorithms."

The Return of Corporeality

NAU's history emphasizes "Action." Wang Mu-Ti's creative process is full of extremely high-intensity physical labor. Facing a 4-meter-high paper, the artist must use the muscles of the whole body to control the brushstrokes and the flow of pigments.

In Form as Emptiness, that huge black mass is actually the crystallization of the artist's physical labor. It is the sediment of time, the proof of human will forcibly intervening in the material world. This forms a sharp contrast with the action of "clicking a mouse" when AI generates images.

The True Meaning of Renritsu: Establishing Subjectivity in the Data Torrent

The "Renritsu" (Alliance) touted by NAU refers to the coexistence of independent individuals. In an era where algorithms attempt to homogenize human aesthetics and big data attempts to predict our preferences, Wang Mu-Ti uses these extremely personalized, extremely handmade, and extremely huge physical works to defend the subjectivity of the artist. He proves that even in the digital age, the warmth of human handiwork, imperfection, and massive physical presence still possess an irreplaceable sanctity.

Digital Dialectics of the Trilogy — Re-reading the Visual Masterpieces

When we gaze at Wang Mu-Ti's three masterpieces again with the perspective of "Digital vs. Physical," we find they possess a brand-new dimension of interpretation.

1. Form as Emptiness: The Black Hole of Pixels

- Interpretation: The black mass formed by stacking ink and acrylic in the center of the image can be seen as a "Data Black Hole." It is heavy and dense, absorbing all light and information. The pink-purple gradient in the background carries a strong "Digital Neon" texture, symbolizing the lightness and illusion of the virtual network.

- Metaphor: This painting displays the existential state of contemporary people—our physical bodies stagnate heavily in the physical world (black rock), while our spirits float in weightless cyberspace (pink-purple background).

2. Numinous Realm: Alishan: Uncoded Nature

- Interpretation: This is a landscape that refuses to be coded. Wang Mu-Ti uses extremely complex stacking of ink and acrylic to create a "High Noise" visual effect. These noises are not errors, but the essence of nature.

- Metaphor: In the eyes of AI, Alishan might be just a set of green data models; but under Wang Mu-Ti's brush, it is an organism full of scars, history, and unpredictability. This is the most affectionate physical backup of "Nature."

3. Light of the Middle Way: The Sublimation of Interface

- Interpretation: That violet-white band of light traversing the image is very much like the afterglow before a digital screen turns off, or the "Interface" between virtual and reality.

- Metaphor: The black-gold chaos above and below represents cluttered information anxiety, while the band of light in the middle is the clarity after passing through the information fog. Wang Mu-Ti proposes a "Middle Way for the Digital Age" here: We should not flee technology, nor should we drown in technology, but should find a balance point for the soul between the virtual and the real.

Unfinished Alliance, Eternal Subject: Cultural Breakout from Taiwan

—— The Cultural Politics of Wang Mu-Ti’s Solo Exhibition: Establishing a "Taiwanese Heterotopia" at the National Art Center, Tokyo

When we return from the micro-interpretation of works to a macro-cultural perspective, we find that Wang Mu-Ti's solo exhibition at the National Art Center, Tokyo, holds cultural-political significance beyond art itself. This is not just an artist's success; it is a "Cultural Event."

In the past, the discourse of Asian contemporary art was often dominated by the West or Tokyo, with artists from other regions often in a peripheral position of "being watched." However, Wang Mu-Ti's participation strategy—intervening in a large-scale public entry exhibition with "Solo Exhibition Specifications"—completely overturns this power structure. He is no longer a participant seeking recognition, but a "Interlocutor" with a complete worldview.

Geopolitical Scrutiny — Refusing the Periphery, Establishing Coordinates

Wang Mu-Ti's choice to join NAU and become its first Taiwanese member demonstrates high strategic vision. He uses this special mechanism of a "solo show within a group show" to establish a cultural subject coordinate belonging to Taiwan in Roppongi, Tokyo.

The Presence of the Taiwanese Subject

- Massive Physical Existence: He does not just hang a few paintings, but occupies the line of sight in physical space with three giant works nearly 4 meters tall. This "Monumental" display is itself a strong declaration.

- Cultural Confidence: Through Numinous Realm: Alishan, he transforms Taiwan's landscape memory into a universal spiritual experience; through Light of the Middle Way, he demonstrates the interpretive power of Eastern philosophy in contemporary abstract painting.

Establishing "Heterotopia"

French philosopher Michel Foucault proposed the concept of "Heterotopia," referring to constructing a real yet distinct space within real society. What Wang Mu-Ti establishes in Exhibition Room 1A of the National Art Center is precisely a "Taiwanese Heterotopia."

- In this space, Numinous Realm: Alishan directly implants the sublimity and temporality of Taiwan's high mountain sacred trees into the urban center of Tokyo. Millennium-old ink traditions coexist with contemporary acrylic media. This is not an imitation of Japanese scenery, but a display of confidence in Taiwan's landscape.

- Form as Emptiness and Light of the Middle Way show how Taiwanese artists digest Eastern ink and Western acrylics to create a unique visual language.

He proves that as long as Taiwanese artists dig into the roots of their own culture and possess the ability to master huge scales and cross-media, they can stand in the center of the world stage without having to be anyone's vassal.

NAU’s "Renritsu" as a Strategic Fulcrum

NAU inherits the rebellious spirit of Masunobu Yoshimura's "Neo-Dada" from the 1960s. Its core philosophy "Renritsu" (Alliance) emphasizes: No center, only nodes; no hierarchy, only coexistence. Wang Mu-Ti does not need to imitate Japan's mainstream "Nihonga" or cater to Western "Conceptual Art." Under NAU's Alliance framework, relying on three masterpieces approaching 4 meters, he directly declares the "On-site" presence of Taiwanese art.

The Return of the Curator-Artist — Resisting "Fragmentation" with "Structure"

In an era of fragmented information, the answer Wang Mu-Ti gives is: "Structure" and "Depth." This is also an answer sheet he submits to the contemporary art world as a "Digital Museum Project Director."

Physical Translation of Digital Thinking

As an expert who has long built cloud databases, Wang Mu-Ti knows the importance of "Structure." He also demonstrates this structural thinking in physical painting.

- The tripartite composition of Light of the Middle Way is like a rigorous data architecture: Chaos at the top (Input), Noise at the bottom (Interference), Band of Light in the middle (Core Processing and Output).

- He elevates painting from simple "emotional expression" to the level of "rational architecture." This is a kind of "Intellectual Art" that requires the audience not only to see with their eyes but to decode with their brains.

Resisting the Mediocrity of Algorithms

Facing the proliferation of AI-generated images, Wang Mu-Ti resists with "Massive Physical Mass."

Algorithms can easily generate a perfect image, but they cannot generate a sheet of Large-format Gasen paper 142 cm wide and 399 cm long, bearing the thickness of ink permeation and acrylic stacking. This physical "irreproducibility" is Wang Mu-Ti's defense of the artistic Aura.

Future Revelation — The New Avant-Garde is "Inward"

Looking back at NAU's history, from Masunobu Yoshimura's "Outward Explosion" on the streets in the 1960s to Wang Mu-Ti's "Inward Gaze" inside the museum in 2026, we see a trajectory of avant-garde art evolution.

From Destruction to Construction

Early avant-garde art aimed to destroy the old aesthetic order. The new generation of avant-garde represented by Wang Mu-Ti is carrying out "Spiritual Reconstruction" on top of digital ruins. He no longer angrily attacks the system but gently and firmly constructs a spiritual space capable of settling the body and mind. He uses the "State Apparatus" of the National Art Center to transmit a personal, intimate, and spiritual sublime experience.

The Victory of Interdisciplinarity

Wang Mu-Ti's success foreshadows the victory of the "Interdisciplinary Artist." Future artists may all need to be like him, possessing both "The Intellectual Depth of a Digital Expert" (like his archival consciousness) and "The Touch of a Physical Artist" (like his control of ink and acrylic). Pure visual pleasure is no longer enough to move people; only the weight of thought can stand firm in the torrent of information.

Finding the Soul’s Anchor in the National Art Center, Tokyo: Wang Mu-Ti’s Creative Monologue

—— An Exclusive Interview with Taiwan’s First Solo Exhibition Artist at NACT: On Scale, Media, and the "Sublime" that Cannot be Digitized

Dialogue — Why Must it be "Four Meters"?

Q: In such a huge venue as the National Art Center, Tokyo, you chose three masterpieces approaching 400 cm in height. This is a very risky decision. What was the consideration behind it?

Wang Mu-Ti: "Scale itself is a language. The ceiling height of the National Art Center exceeds 5 meters; it is an industrial-level 'White Box.' Here, ordinary paintings get swallowed by the space like postage stamps. As the first member from Taiwan to hold a solo format here, I couldn't just 'display,' I had to 'confront.'

The 399 cm height of Numinous Realm: Alishan is not to show off technique, but to restore that sense of 'looking up' I felt at the foot of the Alishan sacred trees. That smallness and awe of humans before nature can only be reconstructed in the urban center of Tokyo through this Monumental Scale. I want the audience's bodies to be forced to slow down and their line of sight forced upward the moment they walk into the exhibition area. This is the intervention of physical space upon psychological space."

Dialectic of Media — Ink's "Time" and Acrylic's "Space"

Q: These works use a lot of "Xuan Paper/Large-format Gasen Paper" combined with "Ink and Acrylic Paint." These two media are almost conflicting in their attributes. How do you handle this relationship?

Wang Mu-Ti: "That conflict is exactly what I want. I am a person of the digital age; we are used to the harmony of RGB light on screens, but the real world is full of noise and conflict.

- Ink is 'Time': It permeates and spreads on Xuan paper; that is an irreversible process, representing Eastern fluidity and historical sense.

- Acrylic is 'Space': It dries fast, has strong coverage, and possesses Western materiality and modernity.

In Form as Emptiness, I used ink to stack up that heavy black rock (Karma), and then used acrylic paint with a pink-purple neon feel to surround it, to crash into it. The 'permeation' of ink and the 'coverage' of acrylic gaming on the same sheet of paper is just like our contemporary situation—the soul still lingers in ancient traditions, but the body has been thrown into rapid digital modernity."

Duality of Identity — The "Physical Counterattack" of a Digital Expert

Q: You are also a senior Digital Museum Project Director, dealing with virtual data all day. How does this background affect your physical creation?

Wang Mu-Ti: "Precisely because I know 'Virtual' too well, I crave 'Physical' even more. In a digital database, a painting is just a file of a few MBs; it is smooth and thickness-less. But when creating Light of the Middle Way, I could feel the resistance of the Xuan paper fibers and smell the mixture of ink and color. These three works are actually my counterattack against 'Algorithms.'

AI can generate a perfect picture, but it cannot generate a sheet of Large-format Gasen paper 142 cm wide and 399 cm long, bearing the thickness of countless stacked brushstrokes. This physical 'irreproducibility' is the 'Aura' of art. I hope the audience comes to Roppongi not to see a picture, but to experience a 'Field'—a physical field constructed jointly by matter, labor, and spirit."

Echo of History — NAU21 and Taiwan’s Coordinate

Q: As the first Taiwanese member of NAU, what significance do you think this exhibition has for Taiwan-Japan art exchange?

Wang Mu-Ti: "NAU's predecessor was the 'Neo-Dada' of the 1960s, which was the golden age of Japanese avant-garde art. To join this genealogy as a Taiwanese and obtain an independent curatorial space, I think symbolizes a kind of 'Level Gaze.'

We are no longer unilaterally accepting Japanese or Western aesthetic standards, but coming here to dialogue, bringing Taiwan's Alishan, Eastern Middle Way thought, and our unique reflection on the digital age.

What I established at the National Art Center is not an exhibition booth, but a 'Taiwanese Heterotopia.' Here, culture has no superiority or inferiority, only Alliance (Renritsu) and symbiosis. I hope these three works can become a coordinate, proving that Taiwan's contemporary art has the ability to emit its own clear and loud voice in a world-class hall."

Prophecy of the Future

As the solo exhibition concludes in February 2026, what Wang Mu-Ti leaves in Tokyo is not just three masterpieces, but a profound question about "How Art Returns to the Sublime." In an era where everything can be NFT-ized and AI-generated, Wang Mu-Ti chose the hardest path: Massive scale, difficult-to-control fluid media, and extremely high-intensity physical labor. He uses the calm of a "Digital Expert" to discern the limits of the virtual; and the passion of an "Avant-Garde Artist" to embrace the temperature of matter. This solo exhibition at the National Art Center is a milestone in Wang Mu-Ti's artistic career and an important breakout for Taiwan's contemporary art moving towards the international core stage. Just like the Light of the Middle Way piercing the fog in his painting, this exhibition points out a direction regarding "Depth" and "Reality" for confused contemporary art.

Architecture on Paper: Deconstructing the Technical Texture of Wang Mu-Ti’s Four-Meter Masterpieces

—— How Taiwan’s First Solo Exhibition Artist at NACT Reshapes the Physicality of Contemporary Ink with "Ozu Washi" and "Acrylic"

In Exhibition Room 1A of the National Art Center, when viewers get close to Wang Mu-Ti's three masterpieces, they will be surprised to discover: the black masses that look like stele from afar are actually full of countless tiny pores, flows, and stacks up close. This is not the "dyeing" of traditional ink, nor the "daubing" of Western oil painting, but a brand new "Construction."

The core technical achievement of Wang Mu-Ti's exhibition lies in his success in resolving the conflict of "Heterogeneous Media" on an "Extremely Massive Scale," thereby proving the high maturity of Taiwanese artists in contemporary media experiments.

The Will of the Carrier — When "Ozu Washi" Meets Four-Meter Ambition

A highlight of this exhibition is that the work Numinous Realm: Alishan uses Japan's top-tier "Large-format Gasen Paper produced by Ozu Washi."

- Carrier Challenging Limits:

- For ordinary Gasen paper, moisture control becomes extremely difficult beyond 2 meters. Yet Wang Mu-Ti challenges the limit length of 399 cm. Paper of this scale possesses an "Architectural Nature" itself. It is no longer just a plane for painting, but a massive, hanging "Soft Sculpture."

- Cultural Appropriation and Dialogue:

- As a Taiwanese artist, Wang Mu-Ti chooses the most representative traditional Japanese Washi, but paints Taiwan's Alishan sacred trees on it, covering it with Western acrylic pigments. This itself is a strong "Cultural Appropriation" and dialogue. He uses the excellent fiber toughness (long fibers) of Japanese Washi to withstand high-intensity pigment stacking, proving that "Paper" can also exhibit a heaviness like Canvas, yet retain the unique "Breathing Sense" of paper.

Fluid Battlefield — The "Aesthetics of Repulsion" between Ink and Acrylic

The most fascinating details in Wang Mu-Ti's works come from the interaction between Water-based Ink and Acrylic Pigment.

- Hydrophilic vs. Hydrophobic: In Form as Emptiness, he first uses thick ink to permeate the bottom layer on Xuan paper, establishing the depth of black. When it is half-dry, he crashes in acrylic pigment containing gum.

- At this moment, the oily acrylic and the water-based ink wage a microscopic war within the fibers. The acrylic repels the ink, and the ink tries to permeate the edges of the acrylic. This "Repulsion" leaves cracks and sedimentary textures on the surface like crustal movements. This is not drawn by a brush, but a natural topography automatically generated by "Physical and Chemical Reactions."

- Traditional ink seeks "Fusion," but Wang Mu-Ti pursues "Repulsion."

- Contemporary "Broken Ink":

- This can be seen as a radical contemporary version of the traditional Chinese "Broken Ink" technique. Wang Mu-Ti uses the product of the industrial age (Acrylic) to "break" the product of the agricultural age (Ink), creating a visual language that is both ancient and modern, organic and synthetic.

Measurement of the Body — Eastern Deduction of Action Painting

In the history of NAU (New Artist Unit), predecessor Ushio Shinohara emphasized physical intervention with "Boxing Painting." Although Wang Mu-Ti does not use boxing gloves, when facing a painting paper 142 x 399 cm wide, the creative process itself is a high-intensity "Action Painting."

- Whole-Body Brushwork:

- To control the verticality of a 4-meter-long line (like the white beams in Numinous Realm: Alishan), the artist cannot just move his wrist; he must use the core muscle groups of the whole body and even needs to move constantly across the large-scale surface.

- Speed and Control:

- Acrylic dries extremely fast, and ink spreading is extremely uncontrollable. Wang Mu-Ti must make bold decisions in a very short time. This "Sense of Speed" is sealed in the "Flying White" (streaky) brushstrokes at the top and bottom of Light of the Middle Way. That is a direct rubbing of the artist's body energy and physical evidence of establishing "Presence" in the huge space of the National Art Center.

Technique is Concept

Why could Wang Mu-Ti become the First Taiwanese artist to hold a solo exhibition format at the National Art Center?

The answer lies not only in his philosophical depth or cultural discourse but also in his demonstration of the technical ability to "Master Massive Matter." He turns fragile paper into solid stele, and conflicting pigments into a harmonious field. This ultimate control over media qualifies him to be not a passive participant, but an active "Space Constructor" in this highest-level art hall in Asia. Through these 4-meter masterpieces, Wang Mu-Ti shows the world: Taiwan's contemporary ink art has evolved beyond the desktop elegance of "Literati Painting" into a powerful art form with "Publicness" and "Monumentality."

He is an "Intellectual Artist" thinking about structure with a scholar's brain; he is a "Digital Curator" preserving aura with archival consciousness; he is also a "Physical Defender" anchoring a heavy and real physical coordinate for this increasingly virtual world with massive paper and pigments.

This is not only Wang Mu-Ti's personal victory but also a confident and perfect "Presence" of Taiwan's contemporary art on the international stage. In Exhibition Room 1A of the National Art Center, Wang Mu-Ti's exhibition area gives a strong somatic sense of "Looking Up." The three masterpieces—Form as Emptiness, Numinous Realm: Alishan, Light of the Middle Way—all present an extremely elongated vertical proportion (height approx. 390-399 cm, width approx. 140 cm).

The choice of this proportion is by no means accidental. In contemporary art, horizontal Landscape usually represents narrative and scenery, while vertical Portrait represents portraits and inscriptions. Wang Mu-Ti chose the latter, but he depicts not people, but "Portraits of the Spirit."

Verticality as a Resistance

In today's digital media-dominated world, human visual habits are locked in "Horizontal Scrolling" (except for Instagram Stories, most information flow is still horizontal reading or short scrolling).

- Reversing Visual Power: When the audience stands in front of Numinous Realm: Alishan, their line of sight cannot capture the whole picture at once. They must first see the heavy texture at the bottom (Land/Foundation), then slowly move up, passing through entangled ink marks (History/Time), and finally reach the white lines piercing the mist at the top (Light/Spirituality).

- This viewing process itself is a "Pilgrimage." Wang Mu-Ti uses physical scale to let the audience reenact the bodily experience of climbing Alishan in the exhibition hall.

- Wang Mu-Ti's masterpieces, nearly four meters high, force the audience's eyeballs to perform a "Large-Scale Vertical Scan."

- Contemporary Translation of Eastern Scrolls:

- This elongated proportion echoes the traditional Eastern "Hanging Scroll." But he abandons the blank space and lightness of traditional scrolls, using the heavy stacking of Acrylic Pigment and All-over composition to fill every corner. This transforms the "private scroll of the literati" into a "public monument."

Phenomenology of Ink — "Black" is Not a Color, It is Space

In Wang Mu-Ti's works, Black occupies a dominant position. But the "Black" he uses has a dual attribute: both the "Carbon Sense" of traditional Pine Soot Ink and the "Plastic Sense" of modern black acrylic.

- Light-Absorbing Black Hole: Unlike Malevich's Black Square, Wang Mu-Ti's black is organic and breathing. It symbolizes the "Ultimate of Matter"—all karma, memories, and history settle here.

- In Form as Emptiness, that huge suspended mass is not flat black. Wang Mu-Ti uses the permeability of ink on Xuan paper to create countless tiny pores. These pores absorb the light of the exhibition hall, giving the black a kind of "Infinitely Receding Depth."

- Weight of Matter:

- In Numinous Realm: Alishan, ink color and dark green acrylic interweave, forming a heavy texture like the bark of a thousand-year-old sacred tree. The black here is no longer nothingness, but the "Weight of Time." It gives the thin Gasen paper a visual mass like cast iron or rock.

Digital Neon — The Temptation of the Virtual

If "Black" represents heavy reality, then the "Neon Color Scheme" Wang Mu-Ti uses in the background processing points directly to contemporary virtual experience.

- Artificial Gradient: This color is "Inorganic" and "Luminescent." It forms a drastic "Visual Contradiction" with the rough, light-absorbing black ink mass in the foreground.

- In the background of Form as Emptiness, Wang Mu-Ti uses acrylic pigments to create a soft gradient of Magenta and Cyan. This color scheme is common in "Cyberpunk" or digital interface design.

- Collision of Symbols: The result is: That heavy black rock floats awkwardly and lonely in the beautiful but illusory digital neon. This precisely depicts the situation of contemporary people—our physical bodies are heavy, but we live in a world of light pixels.

- This is a clever rhetoric. The artist does not criticize the digital age but juxtaposes "Ancient Ink Black (Pre-modern)" with "Artificial Neon Light (Post-modern)."

Metal and Light — The Interface between Secular and Sacred

In the final chapter of the trilogy, Light of the Middle Way, Wang Mu-Ti introduces a third key color: Metallic and White.

- Restless Metal:

- At the top and bottom of the picture, he uses golden and bronze acrylic pigments with metallic luster. These pigments reflect light as the audience moves, producing an unstable, restless visual effect. This symbolizes the "Conventional Truth"—the material world full of desires and flux.

- Absolute White: In color psychology, this white symbolizes "Purification" and "Order." It cuts off the restlessness of the metallic colors at both ends, establishing an absolutely rational balance point. This is what Wang Mu-Ti calls the "Middle Way"—leaving a streak of white silence amidst the clamorous colors.

- Contrasting with it is the horizontal "Violet-White Band of Light" in the middle. The white here is smooth and Matte; it does not reflect light but emits an inner sense of tranquility.

Collusion of Light and Shadow — The Venue Blessing of NACT

These color strategies of Wang Mu-Ti are maximized in the special exhibition environment of the National Art Center, Tokyo (NACT).

- Intervention of Natural Light:

- NACT's glass curtain wall introduces natural light. During the day, as sunlight falls on Numinous Realm: Alishan, the layers of ink become extremely rich, as if seeing moss deep in the forest.

- Dramatic Spotlight: Wang Mu-Ti clearly calculated the effect of "Light" on "Media." He is not applying color to the canvas, but "Dispatching Light." He allows the works to display a dynamic balance of "Matter (Ink)" and "Illusion (Acrylic)" under different lighting environments.

- In the evening, the venue's artificial Spotlights turn on. At this time, the metallic acrylic pigments in Light of the Middle Way begin to flicker, while the white band of light in the middle appears even more profound.

Visual Spectrum of the New Era

Wang Mu-Ti's color performance in Roppongi, Tokyo, breaks the stereotypes of "Taiwanese Art" or "Ink Art." He does not stay in the traditional ink "Black, White, Gray," nor does he get lost in the Western abstract "Color Explosion." Instead, he extracts an "Intellectual Color Spectrum":

Using Ink to anchor the weight of history, using Neon to metaphorize digital nihilism, using Gold and White to dialecticize the secular and the sacred.

This first Taiwanese solo exhibition artist at the National Art Center, Tokyo, uses these three sets of color symbols to draw a philosophical map regarding "Existence, Virtuality, and Transcendence" for Asian contemporary art in 2026.

- Artist: Wang Mu-Ti (WANG MUTI)

- Core Spectrum:

- Existential Black: Pine Soot Ink + Carbon Black Acrylic — Symbolizing Matter, History, Karma.

- Digital Neon: Fluorescent Pink, Cyan Gradient — Symbolizing Virtuality, Lightness, Illusion.

- Metallic & White: Gold, Bronze, Titanium White — Symbolizing Secular Desires and Sacred Order.

- Exhibited Works:Form as Emptiness, Numinous Realm: Alishan, Light of the Middle Way

- Location: The National Art Center, Tokyo, Exhibition Room 1A

The Silent Anchor in a Fluid Era: The Historical Verdict of Wang Mu-Ti’s Solo Exhibition

—— Summarizing how a Taiwanese artist left an "Indelible" spiritual scale at the National Art Center, Tokyo

Wang Mu-Ti laid out the plan with the macro vision of a "Curator," captured the anxiety of the times with the sensitivity of a "Digital Expert," and finally completed the most primal, most difficult physical resistance with the hands of an "Artist."

The Victory of Matter — Resisting the Era of "Lightness"

Italian writer Italo Calvino praised "Lightness" in Six Memos for the Next Millennium. However, in the "Ultra-Light" era of 2026, where information overloads and images abound, "Heaviness" has instead become a scarce quality.

Wang Mu-Ti's victory is primarily a "Victory of Matter."

- In a world where everything can be clouded, he insisted on moving massive paper, mixing viscous acrylics, and grinding black pine soot.

- The heavy black rock in Form as Emptiness is like a huge "Physical Anchor" thrown ruthlessly into the drifting digital ocean. It tells the audience: Reality has weight, memory has texture, and the sublime requires looking up.

Cross-Domain Fusion — The New Language of "Ink Acrylic"

In the long river of art history, Eastern ink and Western oil painting (or acrylic) have long been in a state of gazing at or even confronting each other. But Wang Mu-Ti achieved a "Symbiosis neither humble nor arrogant" on Gasen paper approaching 4 meters.

- Refusing Binary Opposition:

- He did not let ink submit to acrylic, nor did he let acrylic simulate ink. In Numinous Realm: Alishan, ink is responsible for "Permeation" and "Time," while acrylic is responsible for "Coverage" and "Structure."

- Taiwan’s Hybrid Aesthetics:

- This Hybridity itself is a metaphor for Taiwanese culture—inclusive and flexible in transformation. He created a new language that is neither traditional ink nor Western abstraction; we might call it "Post-Digital Material Expressionism."

Establishment of Coordinates — The "Presence" of Taiwanese Art

The most important point lies in the establishment of "Cultural Subjectivity." As the First Taiwanese Member of NAU, Wang Mu-Ti did not choose to be a quiet bystander. He used the world-class amplifier of the National Art Center, Tokyo to loudly tell a story belonging to Taiwan.

- Light of the Middle Way is not just a painting, but a powerful statement of Eastern philosophy in the context of contemporary art. It proves that Taiwanese artists have the ability to digest the deepest philosophical propositions and transform them into universal, awe-inspiring visual forms.

The influence of these three "Monuments on Paper" Wang Mu-Ti left in Tokyo has just begun. He proved to the world:

- Scale is a weapon against mediocrity.

- Material is the last fortress of the soul.

- Taiwan is an unignorable source in Asian contemporary art.

In this huge "Empty Vessel"—The National Art Center, Tokyo—Wang Mu-Ti successfully implanted a solid core. This is a cultivator, curator, and artist from Taiwan, who, with his wisdom and sweat, wrote a magnificent page for the art history of the 21st century.

From "Yogacara" to "Visual": The Philosophical Engine Behind Wang Mu-Ti’s Masterpieces

—— Analyzing how a "Scholar-Artist" reconstructs the space of contemporary painting with Madhyamaka Dialectics

In Exhibition Room 1A of the National Art Center, when the audience gazes at Wang Mu-Ti's three masterpieces approaching 4 meters, they often feel a "Rational Calmness" beyond vision. This calmness stems from the artist's profound background in Buddhist philosophy.

Different from expressionists who rely on emotional catharsis, Wang Mu-Ti's creation is more like a "Philosophical Deduction." He views the canvas as a place for argumentation and pigments as vocabulary for dialectics. To truly understand these works, we must borrow two keys of thought he has studied for years: Yogacara (Consciousness-Only) and Madhyamaka (Middle Way).

Contemporary Translation of Yogacara — "Everything is Consciousness" in the Digital Age

As a Digital Museum Project Director, Wang Mu-Ti deals with virtual images and data all day. This resonates wonderfully with the "Yogacara" he studies. Yogacara asserts that "Everything is Consciousness-Only," meaning the external world is actually a manifestation of consciousness.

- "Image Aspect" (Nimitta-bhaga) and "Seeing Aspect" (Darsana-bhaga) in Form as Emptiness:

- In the work Form as Emptiness, the suspended black mass symbolizes the "Image Aspect (Object)" in Yogacara—the material object grasped by our senses. The background pink-purple gradient with a digital neon feel symbolizes the "Seeing Aspect (Subject)"—the cognitive projection with subjective color.

- Philosophical Decoding:

- Wang Mu-Ti uses the Heaviness of Ink (Entity) and the Lightness of Acrylic (Virtual) to enact this opposition between "Mind" and "Environment" on the canvas. He tells the audience: In the digital age, the "Reality" we see is often just an "Illusion (Virtual Reality)" projected by algorithms and screens. This painting is a visual critique of the "Digital Yogacara View."

Spatial Dialectics of Madhyamaka — Breaking Binary Opposition

If Yogacara explains "Virtuality," then "Madhyamaka" resolves "Opposition." The core of the Madhyamaka school is Nagarjuna's "Eight Negations of the Middle Way," aiming to break the binary attachments of "Existence/Non-existence" and "Birth/Extinction."

- "Two Truths" Structure of Light of the Middle Way:

- The tripartite structure of the work Light of the Middle Way corresponds perfectly to the "Two Truths" theory of Madhyamaka.

- Black-Gold Restlessness at Top and Bottom: Corresponds to "Conventional Truth," full of chaos, desire, and materiality of the phenomenal world.

- Violet-White Band of Light in the Middle: Corresponds to "Ultimate Truth," symbolizing emptiness beyond language and phenomena.

- Philosophical Decoding:

- Wang Mu-Ti's brilliance lies in allowing these two to "Coexist" on the same sheet of Xuan paper. The band of light in the middle does not eliminate the darkness above and below, but lives with it. This visualizes the profound doctrine that "Nirvana and the World are not distinct." He uses the smooth texture of Acrylic (Band of Light) to cut off the chaotic texture of Ink (Black Gold), formally achieving a "Visual Middle Way."

Phenomenology of the Sublime — From "Visualization" to "Viewing"

In Buddhist practice, "Visualization" is a cultivation of constructing a holy realm through the mind. Wang Mu-Ti externalizes this inner visualization into a 4-meter-high physical painting.

- "Non-Duality of Subject and Environment" in Numinous Realm: Alishan: The texture of the sacred tree covering the picture is both the objective landscape of Alishan (Environment/Yibao) and the projection of the artist's inner spirit (Subject/Zhengbao). Through the massive scale of the Large-format Gasen paper, he invites the audience to enter this field of "Subject-Environment Fusion."

- In Numinous Realm: Alishan, he applies the Tiantai concept of "Non-Duality of Subject and Environment" (Subject and Environment are not two).

- Philosophical Decoding:

- When the audience looks up at this work, they are not just looking at a painting, but performing a "Visual Vipassana (Observation)." Those vertical lines guide the line of sight upward, helping the audience detach from daily trivialities and enter a sublime spiritual state.

The Weight of Intellectuality

In the contemporary art circle, flooded with image consumption and shallow appropriation of concepts, Wang Mu-Ti's appearance is particularly precious. He proves that an artist can be both a "Digital Expert" and a "Buddhist Practitioner." He uses "Yogacara" to analyze the essence of digital virtuality and "Middle Way" to balance the media conflict between ink and acrylic.

What he leaves at the National Art Center is not just three huge paintings, but a complete "Visual Philosophical System." This is the fundamental reason why he, as the First from Taiwan, can receive high praise from the academic and critical circles in this highest art hall in Asia—Because his works possess the weight of thought.

[Exhibition Academic Keywords Recap]

- Philosophical System: Yogacara, Madhyamaka, Tiantai Vipassana

- Core Concepts:

- Image Aspect/Seeing Aspect: Corresponds to Black Rock and Background in Form as Emptiness

- Two Truths (Conventional/Ultimate): Corresponds to Top/Bottom Black-Gold and Middle Band of Light in Light of the Middle Way

- Non-Duality of Subject and Environment: Corresponds to Subject-Object Fusion in Numinous Realm: Alishan

- Exhibiting Artist: Wang Mu-Ti (WANG MUTI)

- Location: The National Art Center, Tokyo, Exhibition Room 1A

From "Participant" to "Definer": The Strategic Blueprint Left by Wang Mu-Ti

—— Post-Exhibition Era Observation: The Rise of Digital Literati and a New Paradigm for Taiwan-Japan Art Exchange

As the exhibition closes on February 15, 2026, Exhibition Room 1A of the National Art Center returns to calm. However, Wang Mu-Ti's (WANG MUTI) action has stirred long-lasting ripples on the level of curation and cultural strategy.

He broke the fate of past Taiwanese artists in international public entry exhibitions—"fighting alone, submerged in the group"—and successfully transformed a joint exhibition booth into an independent "Micro-Museum" through "Massive Physical Scale" and "Profound Philosophical Discourse."

Strategic Paradigm — The Micro-Power Dynamics of "Solo Show within a Show"

What successors should learn most from Wang Mu-Ti this time is his "Spatial Power Dynamics."

- Construction of a Micro-Museum: He used the works themselves as "walls," cutting out a private, high-density spiritual space within the open space. This allowed him to actually possess independent "Solo Exhibition Power" within the NAU exhibition.

- In large Group Shows, artists are usually only assigned a corner of a wall. But Wang Mu-Ti constructed a U-shaped enclosed field through three masterpieces approaching 4 meters.

- Revelation:

- This tells future participants: Don't just go to hang paintings, go to "Create a Realm." On the international stage, only by establishing one's own "Spatial Sovereignty" can one stand out among hundreds of works.

Identity Paradigm — The Birth of "Digital Literati"

Wang Mu-Ti's dual identity—Digital Museum Project Director and Contemporary Artist—defines a brand-new type of artist: "Digital Literati."

- Contemporary Reincarnation of Ancient Literati:

- Ancient Literati were a combination of "Scholar" and "Painter"; they painted to convey the Dao. Wang Mu-Ti inherits this, but the "Dao" he conveys passes through the filter of the digital age.

- Dual-Core Drive of Technology and Thought: This perfect combination of "Left Brain (Digital/Logic)" and "Right Brain (Ink/Spirituality)" allows him to create works that have both contemporary visual impact and can withstand philosophical scrutiny. He proves that future art masters must be "Dual Experts" in technology and thought.

- On one hand, he possesses the rational logic of database construction (rigorous structure, archival consciousness); on the other hand, he possesses the emotional depth of Buddhist scriptures (Middle Way thought, Sublime aesthetics).

Aesthetic Paradigm — Taiwan as a Laboratory for "Media Alchemy"

The exhibited Numinous Realm: Alishan and Light of the Middle Way demonstrate the flexibility of Taiwanese artists in media experiments.

- Victory of Hybridity: This "Hybridity" is precisely the advantage of Taiwanese culture. He shows the Japanese audience: Ink can be very heavy (like oil painting), and Acrylic can be very ethereal (like ink). This "Misreading" and "Reconstruction" of media is the source of innovation.

- The Japanese art scene often has clear barriers (Nihonga vs. Yoga), but Wang Mu-Ti broke the boundaries. He put Ozu Washi (Japan), Pine Soot Ink (East), and Acrylic Pigment (West) into the same furnace.

Here, we complete the comprehensive decoding of Wang Mu-Ti's Solo Exhibition at the National Art Center, Tokyo. From the glory of the venue, technical details, philosophical depth to future strategic significance. At this turning point, we see an artist from Taiwan who refused digital nihilism and embraced the weight of matter; who refused peripheral silence and emitted the voice of the subject.

What Wang Mu-Ti left in Roppongi are three paintings, and also three prophecies:

- The Physical will be more expensive than the Virtual.

- Philosophy will be more charming than Images.

- Taiwan will find its own, irreplaceable coordinate in the world art map.